Groupshow

picking oats with both hands

Project Info

- 💙 Sharp Projects

- 💚 Lisa Jäger

- 🖤 Groupshow

- 💜 Olamiju Fajemisin

- 💛 Bjarke Johansen

Share on

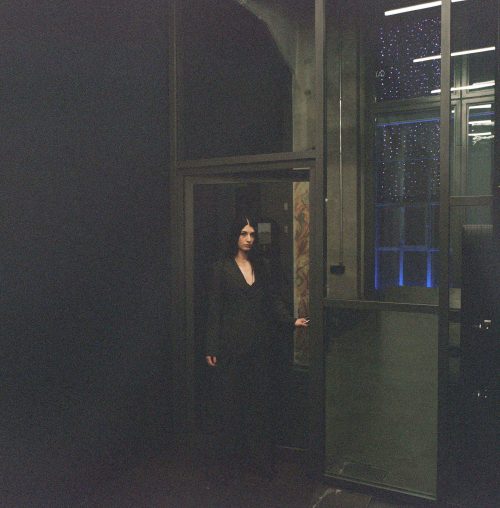

picking oats with both hands installation shot 1

Advertisement

picking oats with both hands installation shot 2

picking oats with both hands installation shot 3

Eva Seiler Frictional Resistance PVC, metal 2023 Lisa Jäger Display for Eva Seiler Frictional Resistance Aluminum 2023

Nikolaus Eckhard, Beim Ausschalen gebrochen, Concrete 2023 & Lisa Jäger Case for Nikolaus Eckhard Beim Ausschalen gebrochen Steel, silicone, styrofoam 2023

Lisa Jäger, Bubblewrap for Tabea Marschall Supporting structures 08 & 09,Silicone, 2023

Eva Seiler, Tränke, Stainless steel 2023

Tabea Marschall Supporting structures 08 Melted glass 2022

Valentino Skarwan Sloth slug love 1 Wool, cord, latex, seeds and ceramic 2020

Valentino Skarwan Sloth, slug love 2 Wool, cord, wood, latex, seeds 2023 & Lisa Jäger Cases for Valentino Skarwan Sloth, slug love 1 & 2 Steel, thermoplastic, silicone 2023

Tabea Marschall Supporting structures 09 Melted glass 2022

picking oats with both hands exhibition, sharp projects facade installation shot

Meltem Rukiye Calisir JUDASOHR- had nature any outcast face Latex, earrings, rhinestones 2021

Lisa Jäger Bartender Ceramics, aluminum, silicone 2023

Lisa Jäger Bartender Ceramics, aluminum, silicone 2023

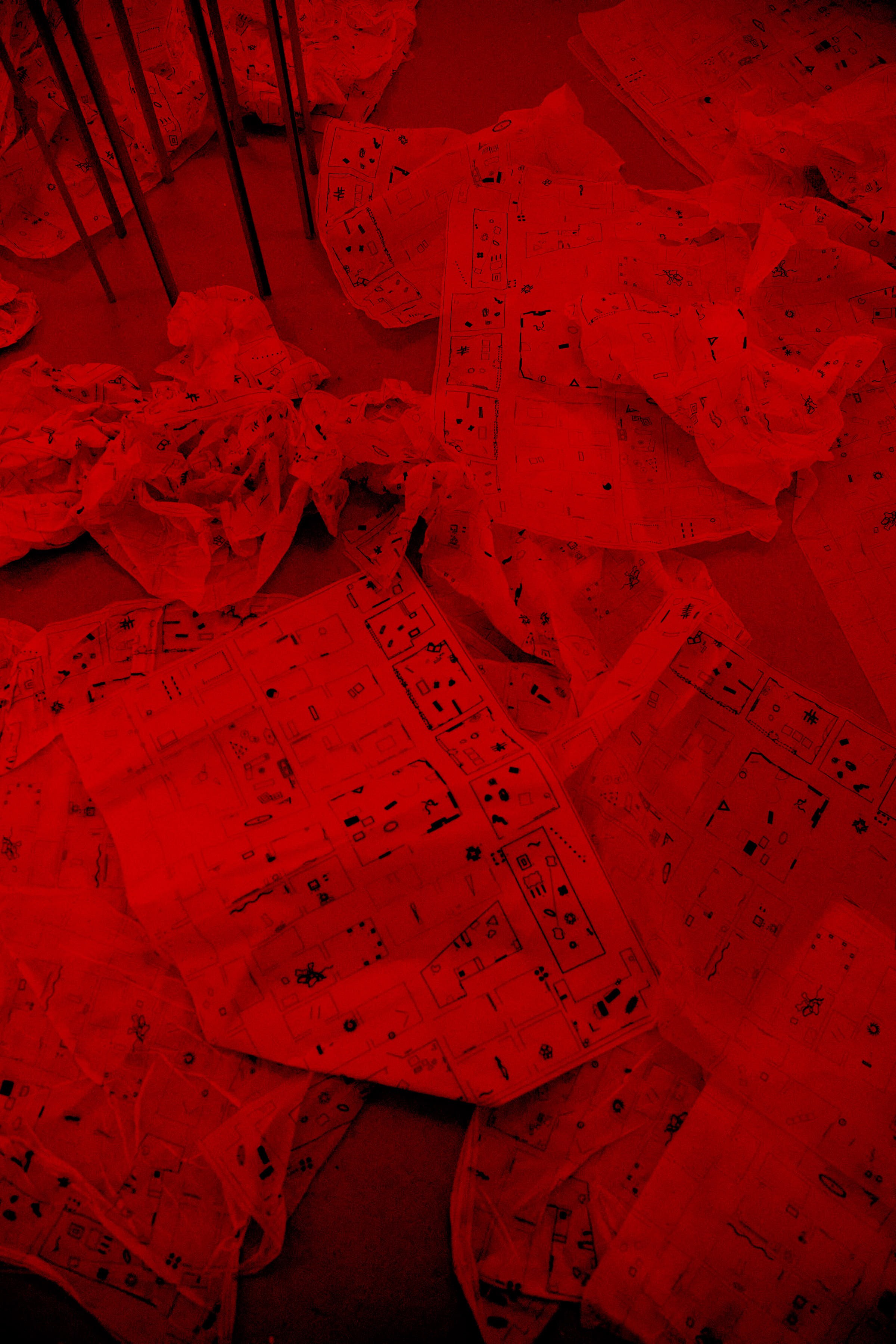

Lisa Jäger Archive Offset print on tissue paper 2017-2023

picking oats with both hand installation shot 4

Lisa Jäger Morel pouch for Meltem Rukiye Calisir JUDASOHR- had nature any outcast face PVC, metal spikes 2023

Lisa Jäger Case for Valentino Skarwan Sloth, slug love 1 Steel, thermoplastic 2023

“…I wrestled a wild-oat seed from its husk, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then another…” —Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”

The project was initiated…

The show was organised…

The work was brought together…

The artist was invited…

Although the origins of the term “to curate” come directly out of thousands of years of expressions around ideas of care, curing, treatment, and responsibility (and the people who take on these rites), we somehow find ourselves at an impasse where the term is quick to be negatively associated—pulled out as a taunt.1 Even in the art world, professionals are increasingly dishing out generative, euphemisms as alternatives Any pre-capitalist notion of care is not only lost but evaded in these attempts to shirk the sentimental and altruistic affect of the ancient verb.

In the spirit of countering this tide of avoidance, the group show “Picking oats with both hands,” tenderly curated by artist and collective organiser Lisa Jäger appropriates the logic underlining Ursula K. Le Guin’s seminal essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” (1986), to instruct a renewed kind of interaction between artist and curator. Taking Le Guin’s assertion that “the earliest cultural inventions must have been [containers] to hold gathered products,” as the main matter of this exhibition, several new and unexhibited works by artists Meltem Rukiye Calisir, Nikolaus Eckhard, Tabea Marschall, Eva Seiler, and Valentino Skarwan, appear arranged among and within sculptures—containers, carriers, cases—of Jäger’s own creation.2

Stepping out of the blind spot obscuring the crossroads between making art and making exhibitions, Jäger’s multiple interventions cultivate a sense of kinship between artist and curator, closer to the origins of the term. The protective objects serve to invoke the invisible processes behind a show—the logistics of transport, storage, installation, et cetera—and to impress the idea of the “carrier bag” as a curatorial concept, and further, opening the notion of medium-as-message.3

1Curate, late fourteenth-century noun, meaning “spiritual guide, ecclesiastic responsible for the spiritual welfare of those in his charge,” from the Medieval Latin curatus, meaning “one responsible for the case (of souls),” from Latin curatus, past participle of curare, meaning “to take care of.”

2 Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” (1986), p.3

3 “In a culture like ours, long accustomed to splitting and dividing all things as a means of control, it is sometimes a bit of a shock to be reminded that, in operational and practical fact, the medium is the message. This is merely to say that the personal and social consequences of any medium—that is, of any extension of ourselves—result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.” in Marshall McCluhan, “The Medium is the Message,” Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), p.1

At times in this presentation, the manifestation of Jäger’s concept appears literal. As with the wrapping paper-stuffed plastic vanity case, Morelpouch (2023), made to house a latex sculpture of a wood ear mushroom stuck with piercings and rhinestones, JUDASOHR - had nature any outcast face (2021) by Calisir.4 Known to grow on the elder tree, the wood ear mushroom took the nickname “Judas’s ear mushroom” following the common belief that Judas Iscariot hanged himself from an elder tree after he betrayed Jesus Christ. Such is the first of several “mycophobic” rumours inscribed in culture which denigrate the mushroom.5 Mediating themes of disgust and adornment, the artist considers the “nonbinary aspect of nature at the organismal level,” per their own words. Similarly, a set of one-off cases replete with bolts and specific curves were made for Skarwan’s mixed media wall sculptures of photosynthesising algae-infected sea slugs, Sloth, slug love 1 (2020) and Sloth, slug love 2 (2023), which are inspired by queer and symbiotic encounters more broadly across nature.

Jäger and Seiler’s collaboration is more innocuous. The wall sculptures Tränke and Frictional Resistance (both 2023) are deftly intertwined with Jäger’s aluminium brackets, suggesting the absurd reality of the bonds of “significant otherness” intertwining humans and non-humans.6 Inversely, Eckhard’s architectural beim Ausschalen gebrochen (2023) considers absence with concrete sculptures of nothings—impressions of the unnamed gap between the arm and the side of the body, the artist’s own. (Jäger’s silicon cast of the casts reveals the unattainable detail of the body, now many degrees of separation from its original.)

Gestures of construction continue with Marshall’s supporting structures 08 and supporting structures 09 (both 2022), the notion of the “carrier” is unravelled and regathered. Two glass wall corner guards, or “supporting structures,” flank the segments of wall pinching the space in the middle. Installed at head height, these temporary scaffoldings disrupt the ontology of the “carrier” with their inherent fragility. Despite their form—like Bartender (2023), a final, standalone work by Jäger comprising several, tiny ceramic drinking vessels on an aluminium table and hooks—these works consider the pure grain of necessity at the core of Le Guin’s thesis: that the “bottle [is a] hero,” and the germ of creativity is the container.7

4The offset-printed paper (Archive, 2017-2023) was also used during the packing of all the artworks in this exhibition.

5 Hasmik Djoulakian and Patricia Kaishian, “The Science Underground: Mycology as a Queer Discipline,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience (2020), p2

6 Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (2003) 7 Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” (1986), p.2

During the opening reception there was a performance by Lisa Jäger.

Olamiju Fajemisin