Sasha Auerbakh

LUX

Project Info

- 💙 MQ ArtBox, MuseumsQuartier

- 💚 Elisabeth Hajek

- 🖤 Sasha Auerbakh

- 💜 Elisabeth Hajek

- 💛 Simon Veres

Share on

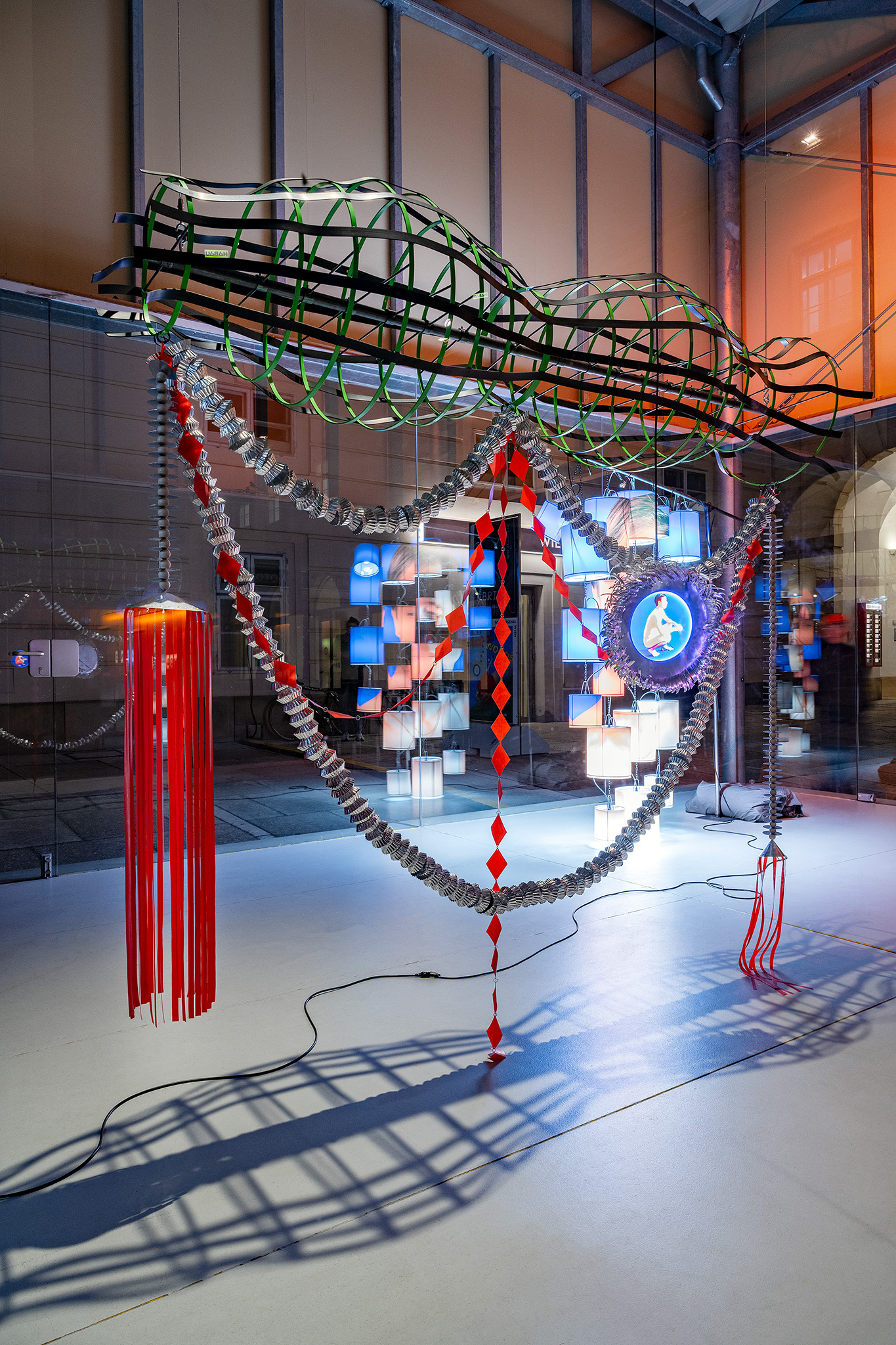

Sasha Auerbakh, LUX, installation view

Advertisement

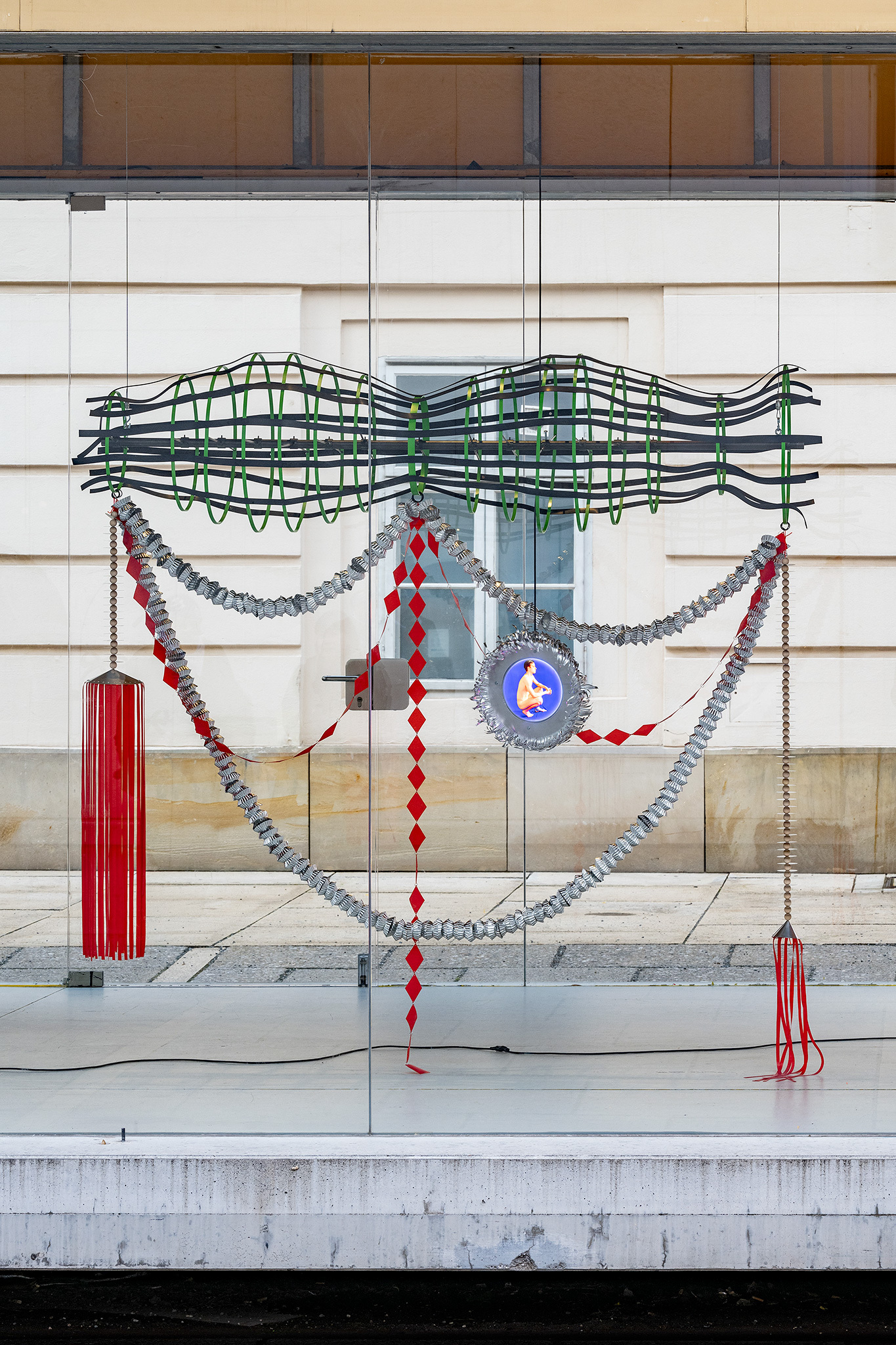

Sasha Auerbakh, LUX, installation view

Sasha Auerbakh, LUX, installation view

Paul R.1 (Amulett), 2024 Steel, paint, wood, plastic, industrial aluminum foil, rubber, magnets, foil laminated on Plexiglas, lamps, cable, 196 x 220 x 50 cm

Paul R.1 (Amulett), 2024 Steel, paint, wood, plastic, industrial aluminum foil, rubber, magnets, foil laminated on Plexiglas, lamps, cable, 196 x 220 x 50 cm

Paul R.1 (Amulett), 2024 Detail

Heti P. 2 (Kamin piece), 2024 Steel, foil laminated on Plexiglas, wood, rubber, LED stripes, industrial aluminum foil, string of lights, electric fireplace, 100 x 154,5 x width variable

Paul R. 2 (Garland), 2024 Steel, lamps, cable, dimmer, print on foil, sandbags, pillowcases, 201,5 x 211 x 20 cm.

Paul R. 2 (Garland), 2024 Steel, lamps, cable, dimmer, print on foil, sandbags, pillowcases, 201,5 x 211 x 20 cm.

Pierre F. (Flower bouquet), 2024 Steel, paint, industrial aluminum foil, UV-print on Plexiglas, lamps, cable, dimmer, 108 x 108 x 237 cm

Pierre F. (Flower bouquet), 2024 Steel, paint, industrial aluminum foil, UV-print on Plexiglas, lamps, cable, dimmer, 108 x 108 x 237 cm

Pierre F. (Flower bouquet), 2024 Detail

Pierre F. (Flower bouquet), 2024 Detail

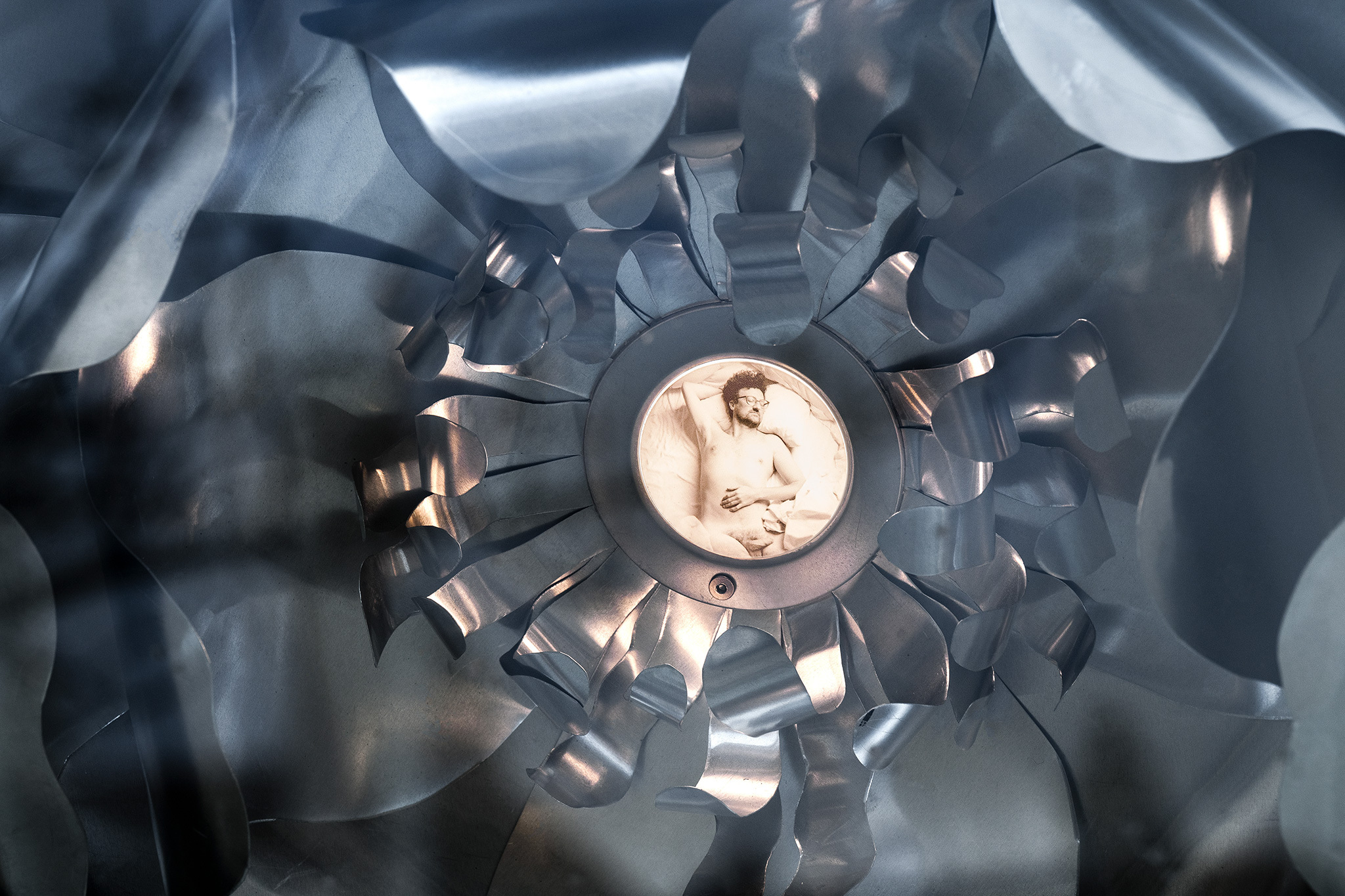

Knife-Hat, 2024 Aluminium, 150 x 150 x 68,5 cm.

Knife-Hat, 2024 Detail

In her installation LUX, Sasha Auerbakh, whose artistic practice is located at the interface of sculpture and photography, shows five sculptural elements that refer to traditional spiritual objects such as amulets and altars and to sacred ornaments of different cultures. The exhibition title alludes on the one hand to the ideational connection between light (Latin: lux), religion, and spirituality, and on the other to the physical integration of light elements into the works.

The individual sculptures communicate with each other by exposing the naked male body, placing it in the spotlight from a feminist perspective, and thus subjecting it to the gaze of everyone. In light boxes and on lampshades, everyday male poses as well as (nude) depictions from art history are referred to, while at the same time, these conventions of depicting male nudity are subverted.

If the male figure is a symbol of patriarchal dominion, the naked male body can be read here as being stripped of its virility. Moreover, by containing it in the form of an amulet, male power is to be done away with.

The objects are in a sense conceived as sculptural amulets with a spiritual effect: they evoke a kind of defensive magic against patriarchal power relationships and structures of oppression. Because these sculptural assemblages pick up on the aesthetics of cult objects, LUX reflects in a playful way what art is capable of and what powers it can develop.

The backlit photographs thus show naked men of various ages in rather passive or submissive poses. They seem to be trapped in the sculptures. In an altar-shaped ensemble, the middle of the triptych displays a naked male body that appears to be grilled by an electric hearth fire beneath the picture; the scene brings to mind Lucifer, the light bearer or, alternatively, the ruler of hell.

In the sculpture Knife Hat, Sasha Auerbakh refers to the turban of a nineteenth-century Sikh warrior, which is decorated with metallic emblems of power and dominance—small daggers, arrowheads, and sabers—and stands for the devotion to the faith. In a different sculpture, objects associated with female housework are arranged in the shape of a garland in order to be used as a weapon in an amulet.

In a sculptural bouquet made of aluminum, a male nude is shown in a floral setting: in the pistil of one of the flowers, the photograph of a peacefully sleeping man can be seen—here, the defensive magic worked.

Elisabeth Hajek