Sylvain Gelewski

Spieglein, Spieglein

Project Info

- 💙 Sihl Delta

- 💚 Camille Regli

- 🖤 Sylvain Gelewski

- 💜 Camille Regli

- 💛 Sebastian Stadler

Share on

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein 1, installation, velvet curtains, lacquer on collected furniture wrapped into scrap canvas and textile, lacquer on collected objects and plaster, blue glass, text, sound, perfume, 300 x 450 x 450 cm, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Advertisement

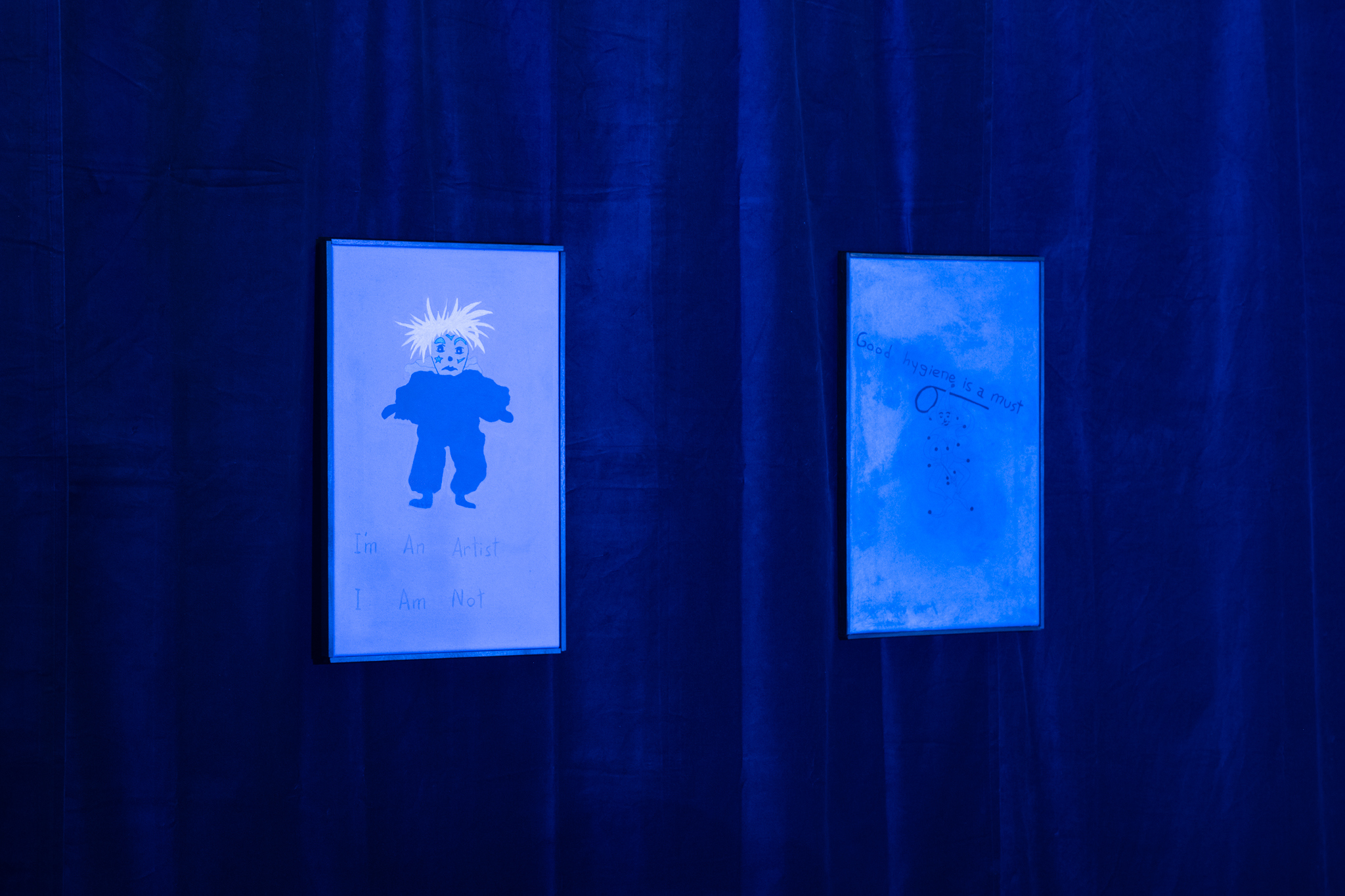

Sylvain Gelewski, The Court Jester 22 (I’m An Artist, I Am Not) & The Court Jester 16 (Good hygiene is a must), oil, acrylic, pencil, marker, Indian ink on canvas, walnut stain on wooden frame, 50.5 x 30.5 x 2.5 cm each, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

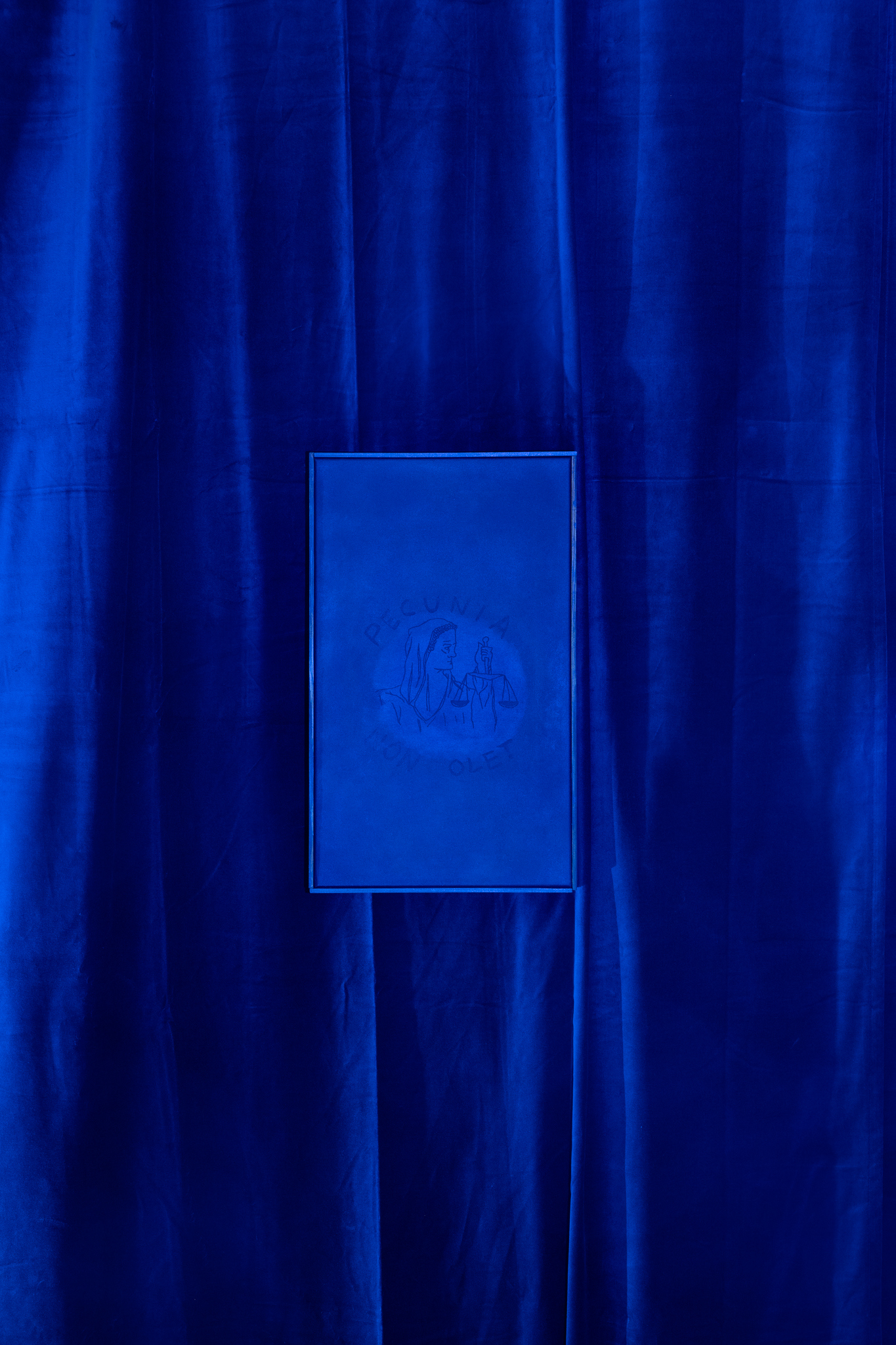

Sylvain Gelewski, The Court Jester 18 (Pecunia Non Olet), oil, pencil, marker, Indian ink on canvas, walnut stain on wooden frame, 50.5 x 30.5 x 2.5 cm, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

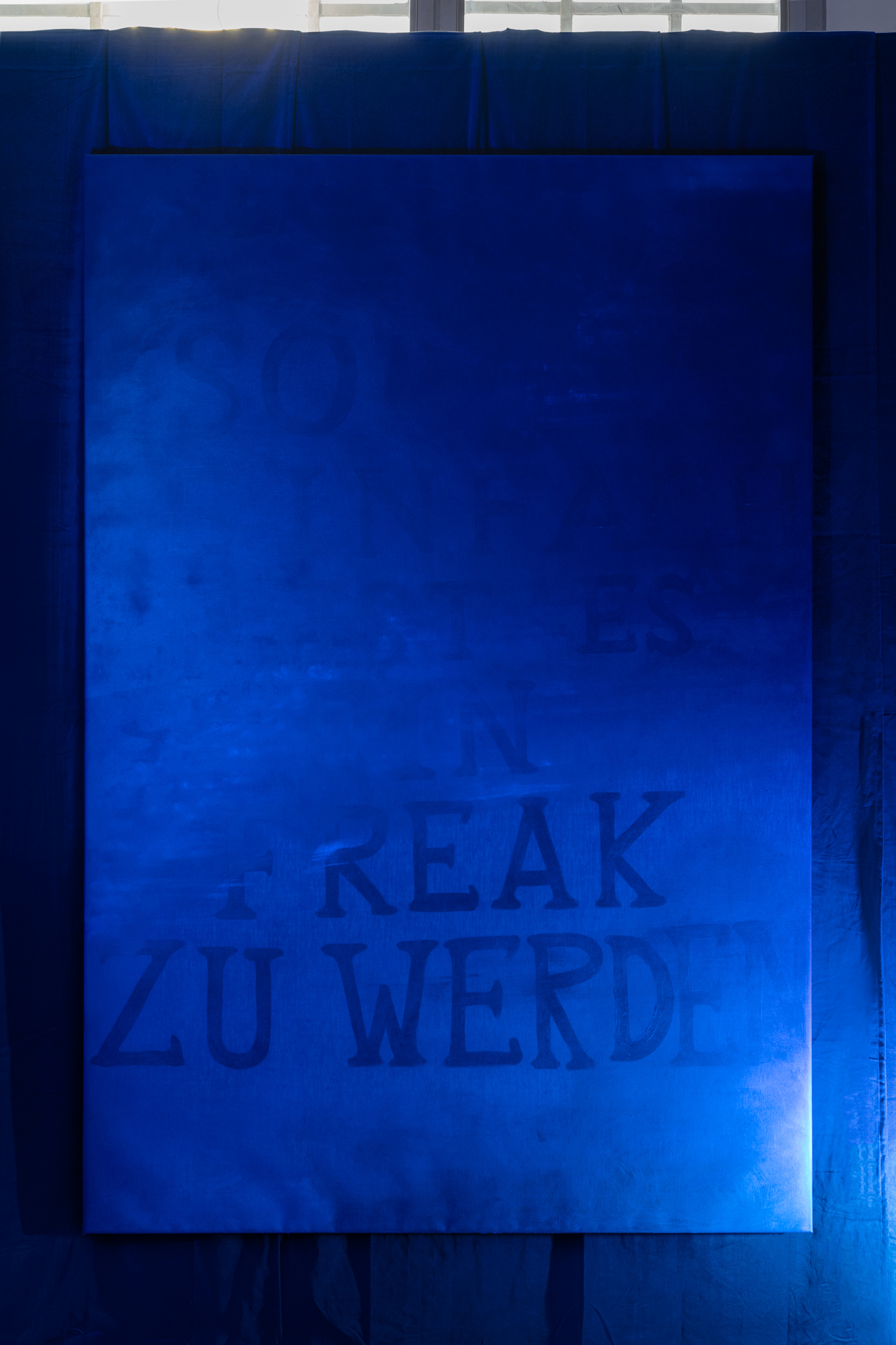

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein 1 (So einfach ist es ein Freak zu werden), oil on linen, 240 x 160 cm, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein 2, installation, cotton curtains, lacquer on collected furniture wrapped into scrap canvas and textile, lacquer on collected objects and plaster, porcelain, text, sound, perfume, 300 x 500 x 500 cm, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, The Court Jester 21 (NORMAL), oil, pencil, marker, Indian ink on canvas, walnut stain on wooden frame, 50.5 x 30.5 x 2.5 cm, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein 2 (Aussi longtemps que je suivrai cette voie, je n’aurai rien à craindre), oil on linen, 240 x 160 cm, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, The Court Jester 17 (Sky is the Limit) & The Court Jester 15 (Vigilance Constante), oil, pencil, watercolour, Indian ink on canvas, walnut stain on wooden frame, 50.5 x 30.5 x 2.5 cm each, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

Sylvain Gelewski, Spieglein, Spieglein, Exhibition View, Sihl Delta, Zurich, 2024

“The mirror does not flatter, it faithfully

shows whatever looks into it,

namely the face we never show to the world because we cover it with the persona,

the mask of the actor.

But the mirror lies behind the mask

and shows the true face.”

– Carl Jung, “Archetype and the Collective Unconscious” (1935)

“Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest

of them all?” Around us, a myriad of billboards and promotional videos bombard us with well-being punchlines, the latest trends and must-have items to buy at any cost. This consumerist frenzy is unsettling, if not anxiety-inducing. Let’s put on our beauty masks, hoping they will disguise our inner conflicts.

Geneva-based artist Sylvain Gelewski spent four months at Sihl Delta, an artist residency space in the heart of Sihlcity, Zurich's vast shopping mall. Inspired by this consumption epicentre, he creates a double-installation with multiple interpretations, perhaps as a strategy of withdrawal or escape from an overly oppressive reality. The two exhibition rooms, juxtaposed and contrasting, embody Zurich's heraldic colours: white and blue. For the artist, this is a given condition for reflecting the host city. An earlier version of this body of work was presented in Sandviken in Sweden in 2023, where the installation Tempus Fugit was displayed in yellow (gold) and blue. Often bridging resonance and dissonance in his work, Sylvain Gelewski evokes the similarities between Sweden and Switzerland; two pseudo-neutral countries vaunted for their image of good students, places of compromise and cleanliness, yet concealing a far more complex reality. Let's put our exemplary right-minded masks back on.

Immersed in a baroque-contemporary setting with scents and sounds, Spieglein, Spieglein brings us face to face with a profound interiority. As words resonate through space, visitors find themselves propelled into the artist's psyche, his inner voices speaking at different levels of consciousness, between childhood memories, fears and existential reflections. The two rooms depict distinct states of mind: on one side, the self's relationship to ambition, social behaviours and superficiality. On the other, a more isolated and introspective voice manifests.

Like a living sculpture, a performer in a white and blue dress, wearing a double mask, traverses the spaces and wanders gently like an apparition. The "persona" - a term deriving from ancient theater that describes the mask worn by actors on stage - becomes the project of a fictitious identity, a social facade worn in public. In Carl Jung’s psychiatrist model of the psyche, the persona lies between the ego and society. Thus, by invoking different sources from Venitian masks to Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, Sylvain Gelewski addresses the ambiguity of identity, what is visible, revealed, or hidden.

All around, objects wrapped in a scrap of canvas recall a "benestante" milieu, where social conventions proliferate. These objects, dehierarchised by their chromatic uniformity, seem to transcend their primary function in favour of an enigmatic staging. Gleaned by the artist in the streets or collected through a non-commercial Telegram group, these objects take on an obsessive character, revealing an emotional ambivalence, but also a recuperating practice intimately linked to artists’ precarious situations.

At the center of the two rooms is a table, a symbol of norms of good conduct which marks the onset of the social game. In a famous scene from Luis Buñuel's film The Ghost of Liberty (1974), the surrealist director overturns bourgeois conventions by undressing his guests and having them sit around a table on toilets instead of chairs. Comedy, with its exaggeration and referential tactics, offers a means of distancing, even extracting from reality. In particular, humour as a critical tool can be used to highlight social dysfunction. Especially cherished by Commedia dell'arte, this genre transforms situations into ridicule, just as it caricatures its characters in extreme archetypes, underlining their often mediocre position on the social ladder.

Within this comedic tradition, the jester, or king's fool, finds its incarnation. The small paintings on the wall from Sylvain Gelewski's series The Court Jester portray various jesters or jokers. Known in the Middle Ages for amusing the noble courts, this marginal figure was uniquely permitted to mock the sovereign. They performed at great banquets, where opulence and extravagance reigned. Queer, marginal, grotesque, neurodivergent (or rather "neuro-diverse" as Sylvain suggests) but essential to social amusement, the fool cynically becomes the antagonistic mirror of a society, revealing its symptomatic use and rejection.

For Sylvain Gelewski, the contemporary jester is today's artist - an emblem of dissidence and marginalisation. And yet, despite a profound desire to break away from conventions, the artist finds themselves instrumentalised by the same system that sustains them. In the entertainment industry, the artist becomes its product but also its prophecy. So, in an

age of fast-paced consumption, technology and quest for life-work balance, isn’t it time to extract oneself and value the benefits of solitude? Amidst the struggle between conforming and subverting, Spieglein, Spieglein confronts us with ambiguities and questions encapsulating the perpetual, interdependent and complex duality: "I’m an artist, I am not ».

After all this, mirror, mirror, do you still dare to judge us?

Camille Regli