Groupshow

sometimes i hold onto the air

Project Info

- 💙 Körnerpark Gallery

- 💚 Katharina von Hagenow, Uladzimir Hramovich, Paulina Olszewska

- 🖤 Groupshow

- 💜 Dear Kubaparis, We are sending you the group exhibition that is still going on in Berlin at the Körnerpark Gallery. We hope you find it interesting to publish.

- 💛 Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Share on

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Advertisement

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Marjorie Brunet Plaza

manchmal halte ich mich an der luft fest

часам я трымаюся за паветра

sometimes i hold onto the air

Belarusian artists in Exile

In 2020, massive civil protests erupted in Belarus, a country between Russia and Poland that was barely on the radar for the West at the time. Directed against the rigged elections and repressive policies of the corrupt head of state, the protests became a cry for freedom and an expression of the desire to live in a democratic nation. Artists and cultural workers were deeply involved in the protests; many were arrested and imprisoned. When released, they fled to Vilnius, Warsaw, Tbilisi, and Berlin to escape further punishment. They had hoped to return soon, but weeks of waiting became months, and months have become years. They have since remained in a state of limbo between two worlds — determined to contribute to change in their homeland while not being physically present and living in a country where their existence is not officially recognised. In the exhibition sometimes i hold onto the air, young Belarusian artists reflect on the contradictions of their situation, looking back at the protests that radically changed their lives and their subsequent years in exile.

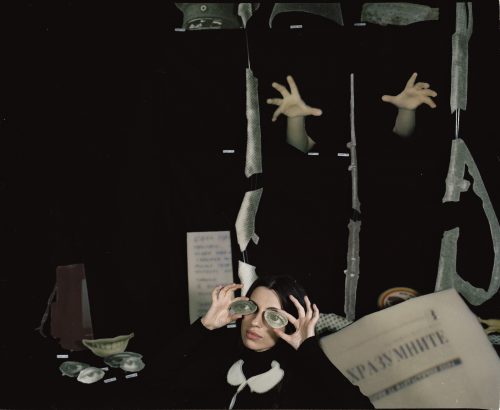

Anastazja Palczukiewicz places her own family history and personal experience of exile in a broader context of displacement and migration patterns between Belarus, Poland and Germany in the first half of the twentieth century. Displaced, a three-part installation, was created in 2023 in Nowa Ruda, Uppa Silesia (Poland), a town populated mostly by Germans up until 1945. After the war, Poles from the east, including what is now Belarus, were settled there. For the installation, Palczukiewicz made casts of wood from an old family apple orchard. Her great-grandfather bought the orchard in the 1950s from people who had moved as part of a resettlement program, leaving their homes in Belarus to live in former German towns. Lesia Pcholka highlights the relationship between the past and present in her work, The Bases. She addresses the tumultuous history of Minsk, where the new autocracy installed an extensive network of surveillance cameras on Stalinist post-war architecture. Pcholka created casts of lamppost bases from the main boulevards of Minsk and mounted cameras on them, symbolizing the regime’s permanent state surveillance, which extends even to those in exile. In Scratches, created in collaboration with Uladzimir Haramovich, the two artists scrape the gold lettering and national emblem from the cover of their passport. This radical gesture demonstrates an irreversible stand against the government of their country of origin.

Under the impact of the 2020 protests, Aliaxey Talstou wrote a poem to the monuments of the city of Brest. If the Past will not end, a video work, shows the artist confronting the monuments, presenting them with his demands for the future of Belarus. In a text recited to the heroes who intended to give the country a glittering future, he speaks of the disappointment and frustration with the current situation and conservative ideologies. “When the past doesn’t end, there are no discoveries, no new worlds, Star Wars is stuck like a blockbuster fairy tale without a vision,” the artist says with bitterness. Artist Antanina Slabodchykava also addresses heroic figures of the past and questions their validity in the present. In her drawings, Helden sind lediglich Helden (Heroes are merely Heroes), she examines the repressive practices of the regime in her home country from a feminist perspective, reflecting on the patriarchal power structures that are deeply rooted in Belarusian society. She also addresses life in exile and the process of assimilation into the new society in which she must now function. In doing so, she alludes to exclusion with a quote from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film Ali: Fear Eats the Soul.

Varvara Sudnik uses traditionally embroidered cloth to describe her experiences of trying to apply for a visa in Germany. Six scenes reveal the absurdities of the bureaucratic processes with topics including borders, work, love, and esteem. In SERVISAS, a 3D animation, embroidered napkins rotate with a tea set on a tray, bearing witness to the endless loops of the visa process and the systematic, successive exclusion. The final scene concludes with the question of how many days are granted before it starts again. In his work, Welcome, Alexander Adamov looks at the expectations placed on him as a migrant. With a fictitious advertising poster promoting himself as the “ideal Belarusian immigrant,” he playfully, and yet with bitter irony, confronts the audience with their own prejudices and expectations towards immigrants in Europe.

Many Belarusians who have had to leave their homeland live in constant motion through different places, changing apartments, cities, and countries. Nadya Sayapina makes the voices of the “others” in her community visible in her works. In her project Temporality, she collects the stories and images of lives “in-between” where a suitcase is the only constant. Images of suitcases in empty apartments and the repeated sentence, “We didn’t plan to leave,” describe the feeling shared by many from her community. She embodies the experiences in her performances from the X Letters project. In My suitcase stands in the corner she attempts to pack herself into a suitcase. In Where are you from?, on the other hand, she moves between images of urban canyons in different cities while Belarusians recite a text in different languages about their experiences of exile based on a poem by Vasilisa Palianina. The question “Where are you from?” remains unanswered at the end.

Handmade black carnations in Rozalina Busel’s work are a reaction to the brutal violence against the civil protests. MOURNING MORNING is part of a long-term project called Borders and Restrictions. Carnations are a traditional symbol of resistance and revolution but are also used in mourning and memorial ceremonies. In Busel’s work, they represent the transition from life to death and the border between the end of life in one place and the beginning of life in another. In this exhibition, the flowers also commemorate the women protesting in Belarus, after which many people had to leave the country. Horror at the regime’s violence is also evident in The Face from the series WHERE ARE THE FLOWERS? by Vasilisa Palianina. A face expresses a cry for freedom but the eyes, framed by flowers, show hope for change. As the artist says: As long as a country is capable of mourning, it is also capable of hope.

The title of the exhibition is from a poem by Belarusian poet Volha Hapaveva, who is also currently living in exile in Germany. In her essay, Die Verteidigung der Poesie in Zeiten dauernden Exils (In Defence of Poetry in Times of Permanent Exile), she invokes poetry and art as a means for free thought and resistance against the bureaucratic language of states and dictatorial violence.

Dear Kubaparis, We are sending you the group exhibition that is still going on in Berlin at the Körnerpark Gallery. We hope you find it interesting to publish.