Theresa Abele, Flora Fritz, Fiene Hauck, Matthias Holznagel, Konrad Jurko, Liz Thérèse Kölbl, Jae Yong Lee, Sojeong Moon, Elli Noëlle, Christoph Nuber, Nicolas Patzer, Antonella Rottler, Lukas Ruster, Aiko Stratmann, Mia Trautmann, Adrian Wußler

BANDS

Project Info

- 💙 Braunsfelder

- 💚 David Ostrowski

- 🖤 Theresa Abele, Flora Fritz, Fiene Hauck, Matthias Holznagel, Konrad Jurko, Liz Thérèse Kölbl, Jae Yong Lee, Sojeong Moon, Elli Noëlle, Christoph Nuber, Nicolas Patzer, Antonella Rottler, Lukas Ruster, Aiko Stratmann, Mia Trautmann, Adrian Wußler

- 💜 Oliver Tepel

- 💛 Mareike Tocha

Share on

Advertisement

BANDS

The Class of David Ostrowski, Karlsruhe Academy of Fine Arts

The plan was to sweep the world off its feet

So you sweep the garage for the neighbours to see

The plan was to set the world on its ear

And I bet you don’t know why you’re here

The Replacements – ‘Happy Town’

They called themselves ‘The Replacements’, which was probably to be understood as ‘The Successors’, whereby they actually saw themselves as ‘The Surrogates’ or ‘The Replacement Parts’. They were a band, but they didn’t want to be what they thought they had to be. And yes, they had a plan.

Only bands can afford to do that: plan the biggest projects in the firm belief that they are actually too late. But such ideas no longer characterise our times – at least you can’t tell from today’s art that young artists lament not having played with Fra Lippo Lippi or Rothko, The French Impressionists or in Cabaret Voltaire. Rather, the focus is on what a band is or should be.

Exposed to the painting support and the weight of their own ideas, the question is certainly appealing to some: how would a band paint?

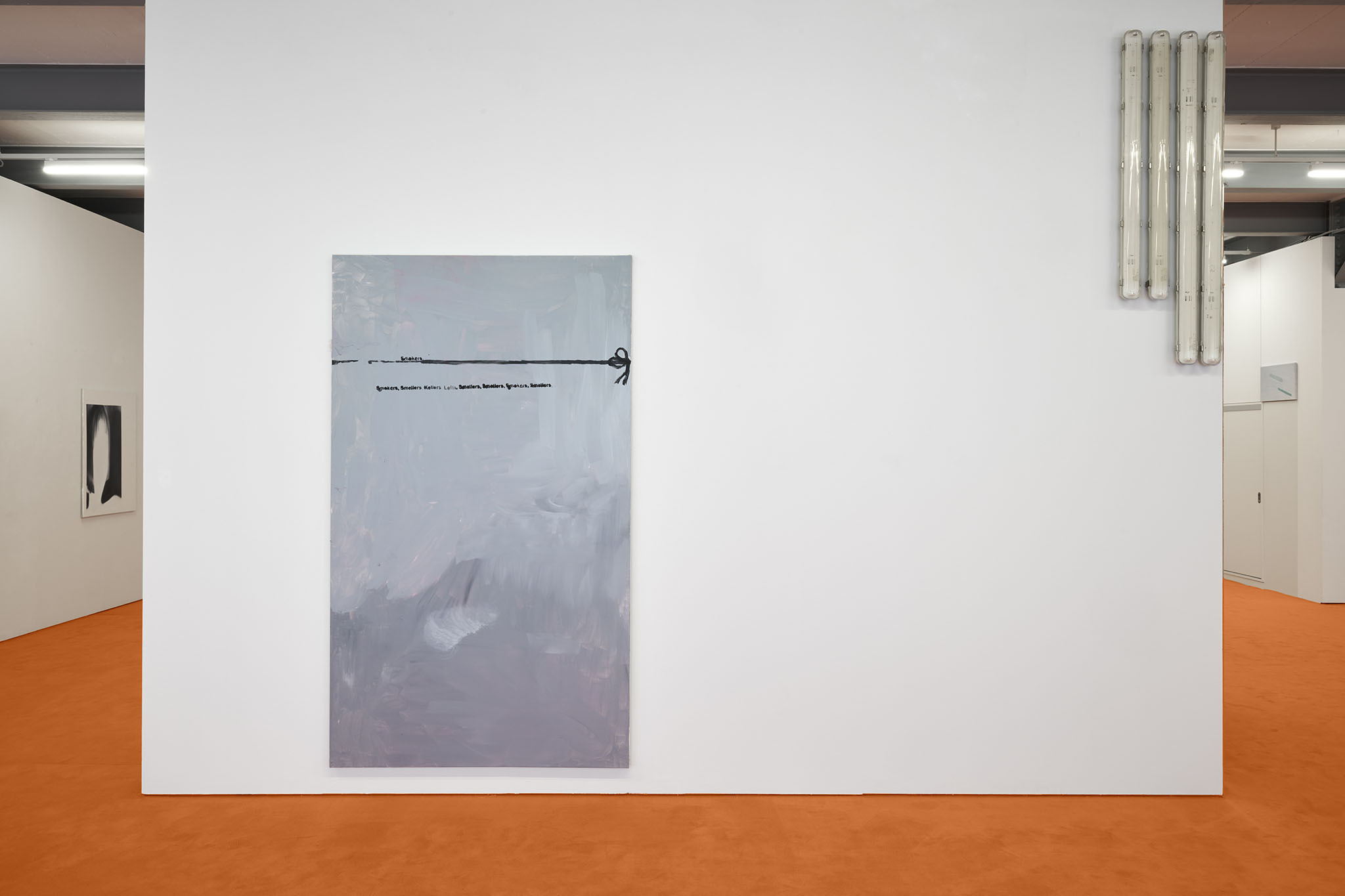

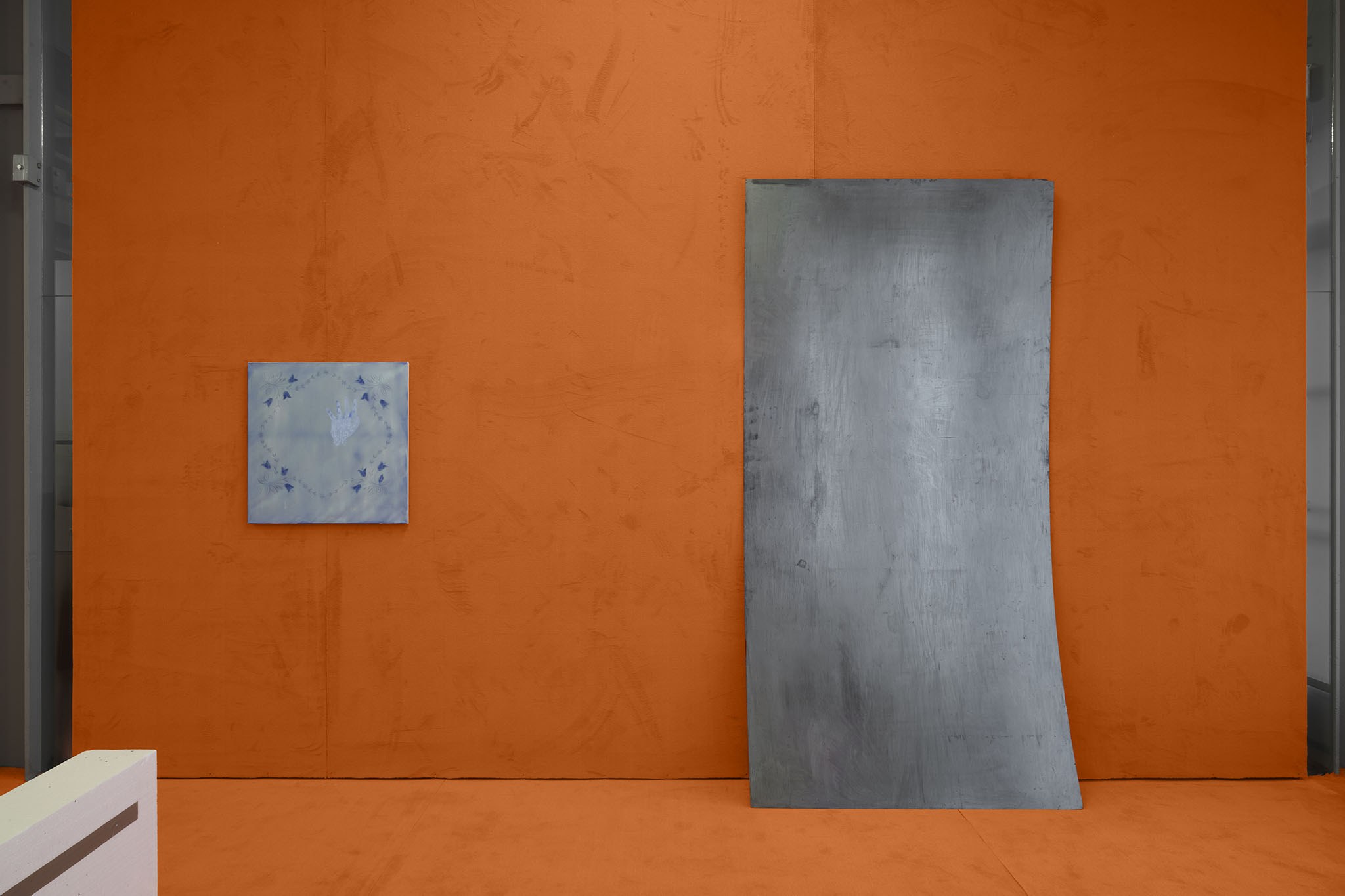

And then they paint, but not like a band. Rather as if each and every one of them had asked themselves: ‘What do I want? Where am I going?’ – This is obvious in the exhibition with its orange floors and walls. The penetrating colour creates a bracket, but it does not have to hold anything together, as nothing necessarily diverges; the orange succeeds in visibly liberating the works from the white grey of the studios.

Liberating, more like releasing a bond, letting go. A romantic vision, as if one were rising into the vastness of the sky. But however romantic or conceptual or unbound the visions may be, letting them go means letting them persist, and that means having said: ‘It’s done’.

There are bands who had their problems with this, who have wanted to add this or that or to do it differently in the studio, and then it even helps if someone confirms: ‘Yes, it’s done’ – and not because the money is running out, but because they firmly believe that it’s right.

Everything is right here, and everything here seems to be in process. Movements everywhere, even where the works claim to be motionless. And it’s the plural, it’s not a ‘movement’, it’s not a trend that might give you answers, that might give you the impression of being in a band.

And the energy is in that plurality. Is it still connected? Figurative, abstract, conceptual, gestural, delicate and seemingly resistant to itself, there is, yes, a sense of harmony, a desire to cry out very quietly, or to search in dynamic forms, or to take a deep breath for a moment and say: ‘I’m probably here.’

The band is responsible for the ‘probably’. It holds, holds the helium ideas, holds the concentration, and also holds the moment. Which brings us back to the dilemma. Because for many bands, the moment is all that remains of their mission to achieve ‘eternity’. Is there such a thing in art as the one great single on a small label that confronts those that were forgotten decades later with the admiring eyes of a much younger audience? – Sadly, all too rarely. I recently saw a work by the outsider painter Robert Schwartz suddenly go for tens of thousands instead of the expected few hundred. Schwartz no longer experienced this, nor the process of people remembering him, showing his works, talking about him, even creating what is called ‘a cult’ in the world of bands. – That’s what I’d like to see in art, and that one could start with this hope.

For artists, a band doesn’t seem like an outdated idea (if you’d asked the same question in 1982, 1993 or 2004, I suspect you’d have got different answers). Nevertheless, for decades now, the world stars of music have again been individual artists. But why would anyone want to be a world star? Maybe to open the eyes of the world? – No, only bands were that presumptuous. Or?

Actually, it would be nice to be able to say something like that. But there are bands that hold art together, that bundle it up and separate it from the hobby painters, from the DeviantArt artists and probably soon from AI. Perhaps the band, the ribbon that holds it all together, is labelled; if you look closely, you will find some text on it, some vexed art history.

And perhaps the band is so free today because it no longer holds such a history. Perhaps there is a freedom in being a band that art is only tentatively working towards. But what is clear is that it is setting off on its way to there.

Sweeping out the studio or garage may not be a sign of conformity, but rather of a new beginning, of getting rid of the dust and, if you have plans, of making it clear that you are not just entrapped. But the art world insists on entrapping its protagonists.

Finding out how not to be entrapped seems to be a visible endeavour. And the denouements, the disengagements – here they play with the orange, with us.

Give the director a serpent deflector

A mudrat detector, a ribbon reflector

A cushion convector, a picture of nectar

A virile dissector, a hormone collector

Phish – ‘Cavern’ (from the album A Picture of Nectar)

Are bands a relic of yesterday? – It doesn’t appear so.

Oliver Tepel

(Translation from German in English by Gérard Goodrow)

Oliver Tepel