Groupshow

Little John

Polina Davydenko, Kutilka, 2022

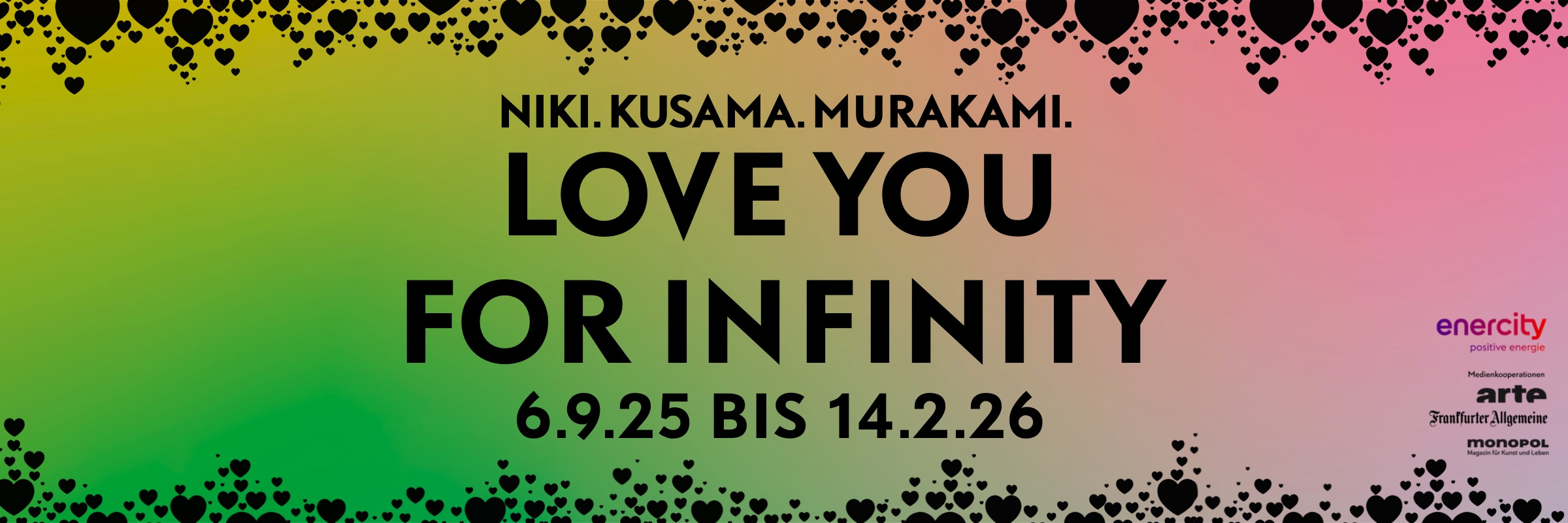

Advertisement

Polina Davydenko, Kutilka, 2022

In front: Anna Hulačová, Dolomite Lovers, 2016 and Denisa Langrová, Lekce feralizace, 2021

Anna Hulačová, Dolomite Lovers, 2016

On the left: Denisa Langrová, Lekce feralizace, 2021 and Anna Hulačová, Dolomite Lovers, 2016

Installation view

Installation view

Diana Lelonek, Ptáci, 2019

In front: Magdaléna Manderlová, A všechno je náhle pták a chce odletět, 2022 and Diana Lelonek, Ptáci, 2019

Installation view

On the right: Dominik Gajarský, Equilibrium, 2017, 2023 edit and Zdena Kolečková, V jezírku pohaslých očí, 2022-23

Zdena Kolečková, V jezírku pohaslých očí, 2022-23

Vladimíra Večeřová, You are the Medicine, 2023

Vladimíra Večeřová, You are the Medicine, 2023

Barbara Benish, Manifest Destiny, 1991

Can art become a partner? Perhaps more faithful than one can imagine. Such partnership can work equally well between humans and animals. You probably imagine dogs, cats, maybe birds or terrestrial reptiles. Sure, only a few of us would like to have a scorpion, ant or bat as a pet (although modernist artist Salvador Dalí is said to have had a bat when he was a kid).

In his essay Why Look at Animals? John Berger introduced a small but crucial contrast between galleries and zoos. The two institutions seem similar in how the visitors move inside – they pass by, stop and continue – from cage (from painting) to cage (to painting). This is why the Little John exhibition is slightly non-chronological. It creates circles in the space in which the artists’ works, side by side, build a new story in dialogue. Berger compared the zoo also to a human concentration camp, psychiatric hospital or prison. Recently, we all had to face involuntary confinement during the pandemic, which restricted our movement and squeezed us into closed apartments, almost without the possibility to look and go outside. Don’t the zoo animals experience similar feelings every day? Limited space, timelessness, detachment from the place followed by “domestication, monitoring and species regulation”.

Let me go back when I wrote about the “partner”. I meant it literally that art can become a partner. Let’s mention the Documenta 13 festival in Kassel, Germany, and Pierre Huyghe’s work Untilled. A dog with a pink leg running around – not captive, full of freedom. The dog was all over the place. Some might have seen him, others not. It was like apparition to John. To whom would it be disclosed? What message does such art deliver? It wasn’t without costs – we had to make effort and chase after the artwork. You could either succeed or miss it entirely. It was great to watch those weary bodies trying to figure out where art begins and ends. The environment itself was not exactly a “white cube”. It wasn’t obvious at first whether we were going after art or if we were on our way to a landfill. There was stubble grass, bushes, puddles, mud along the way... and suddenly the dog appeared and ran away immediately. He. The dog with a pink leg. Did I see right? An encounter and a quick look in the eyes. Pause. The dog was gone.

Pierre Huyeghe relies on events generated by chance. However, there was something inherent about this more-than-human encounter. Realizing that the dog controlled the situation. Equality of species. Partnership between man and animal, between man and art. This artistic experience has become a partner for me too, a lifelong one. The dog landed on my body as a tattoo and turned into an icon. A dog with a pink paw on my leg. The experience changed my way of thinking about nature and symbiosis in a much deeper context of human thinking. And what about Beuys? What was his coyote experience like? How did they communicate? And just as Joseph Beuys (German artist) is a key figure of the 20th century art, I decided he would be the key inspiration for the present exhibition which is inspired by his spiritual essence of phenomenological approach. His performance called I Like America and America Likes Me of 1974 begins with the arrival in America. At the airport, Beuys wrapped himself in felt and was escorted to a room (into a cage) where he was confined for several days with a live coyote named Little John. The act became a symbol of a non-hierarchical relationship between two living entities, openly paying tribute to the animal that was a symbol of the Native Americans. For several days, an ordinary man (the society shaman that Beuys pretended to be) spent time with the wild animal which gradually calmed down until it became the partner to the artist. Or did Beuys, on the contrary, became partner to the coyote? Either way, the essence of a symbiotic relationship between different creatures is trust. Of course, we can look at his work with criticism. Was it necessary to cage a wild shy animal? The bars, behind which the two stayed, were restricting their space. In addition, there was a constant surveillance by the audience ready to intervene and protect the artist, if the situation required. What I observe in the work is animal domestication and colonialization of the native population. To me, the performance also symbolizes respect.

Beuys was healing society’s psychological wounds – or at least was addressing them in his so-called social sculpture. He was not interested in America. He did not find the harsh capitalist machinery inspiring at all. On the contrary, with the act of arrival, he wanted to show that America should start enquiring about its origins. Beuys was interested in animals (e.g., How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, Beekeeping, etc.) as well as plants and natural science. The artist believed in Steiner’s anthroposophy and myth. He believed in nature and cosmology.

Although Beuys is not represented in our exhibition, we refer to him by actively engaging and using the coyote’s name. We are left with its essence and inspiration. As Beuys said: “My entire life has been an advert; however, one day, people should be interested in what I promoted.” Similarly, the exhibiting artists, through their works, refer to the relationship between animals and humans differently. Sometimes dramatically and sometimes poetically, symbiotic relationships are infused with scientific, ethical, activist and artistic contemplation. The exhibition thematizes usurpation of a different kind – domestication when humans dominate over someone else by controlling and supervising their reproduction. It is a relationship that is gradually manipulated, purposefully reshaped to benefit oneself. We pull out the animal of its natural environment and begin to artificially transform it for our own utilitarian needs – quite often for breeding. Despite the fact, that domestication is most often associated with animals, we can see it in plants, bacteria, fungi or humans (native peoples). Zoos undoubtedly contributed to domestication in 19th century when the imperial power was asserting itself. The paradox of such living galleries is that, at first, we got all the species from the wild into cages. Today, we can perceive that individual species function as living relics because a domesticated organism has no chance of surviving after being released into the wild.

The Little John exhibition opens with the works of a Ukrainian artist, who has lived in the Czech Republic for a long time. It is impossible not to come across her work. The yellow curtains will rotate us into the interior, a hiding place or a cocoon, in which we discover a video called Kutilka. Polina Davydenko mixes moving images from a natural history documentary with 3D animation and costume production. The main character is an anthropomorphic recluse wasp, an invisible worker classified as an invasive species. We can see its hard work and rest, always in complete isolation from others. The story carries the metaphor of a person who, because of increasing external forces (destroyed land, domestication, change of the original climate, etc.), has to leave home. Although the man finds a similar space to which he must adapt, he is weighed down by inner rootlessness and sense of injustice. Immigrant, caged animal – is there any hope?

Anna Hulačová follows Polina Davydenko in her subtlety work around another insect species in From Here to Eternity. We can see two figures representing the heterogeneous relationship of a man and a woman in a majestic posture on beehives. The image can be interpreted as an oxymoron to our civilization – the pair represents the technological progress of a society that dominates the beehives just like a man dominates the world. However, there is something wrong with dualism. Both have honeycombs inside the abdomen. With tiny insects having the power to populate the large sculptures, they could gradually multiply within, change the visual form and maybe even mentality of the couple if they were alive. Merging into one body. Nevertheless, Anna Hulačová is interested in the bee as a spiritual symbol from ancient Greece. Long before its domestication, the Greeks believed that the bee was a symbol of immortality. They noticed that bees resided in the cavities of dead bodies. After they flied away, it was believed that the soul flew away too, into the realm of the dead. The concepts of spiritual dimension and death are present also in the work of Vladimíra Večeřová.

Vladimíra Večeřová presents a “cobweb” in a tunnel passage that is supposed to evoke dreaming about bats, a symbol of an unconsciousness (bats were loved by Salvador Dalí, a representative of Spanish surrealism). They also symbolize a connection with the ancestors (which hints at the tragedy of a death in the family). The individual pieces of “cobweb” characterize the ephemeral fluttering membranes of bats wings that fly in all directions when startled. The artist cleans, quilts, cuts and stitches the chemically treated leather to respond to the contrast of the worlds. The toxic material is far from being a leftover of genuine leather, the natural material that leather workers use. With reference to artificial leather, we ask ourselves if we really need all these imitations in our world. In her works, Vladimíra returns to rituals and to the indigenous people who initiated her into purification ceremonies and showed her the magic of plant and natural materials. Her visual artwork is full of contrasts. Although the leather is artificial, it works with waste residues looking for new meanings. At the same time, we can read it as a shadow, spiritual dimension of souls that depart back to the universe.

The circle of “ungulates” is created by Barbora Benish, Hana Nováková and Denisa Langrová.

A distinct element is the hanging genuine cowhide by the artist and activist Barbora Benish. The cow skin resonates with the works of Hana Nováková and Denisa Langrová. It is an important fragment of a living creature that people treat carelessly. Death belongs to life; however, it is necessary to consider whether it is still humane and whether animals do not die too cruelly because of humans. At the same time, there is a certain memory that is gradually created by drawing data into parts of the US map. The work Manifest Destiny reflects the situation of native population, which is gradually disappearing from the world, just like endangered animal species. Their way of living, which respects, listens to nature and to more-than-human communication, is a great gift. Joseph Beuys referred to the indigenous nations in his performance with the coyote (mythological symbol of the Native Americans). At that time, he perceived America as a continent of not much interest and full of negativity. The performance escalated as he left immediately after the event. In Barbora Benish’s work, I perceive a temporal continuity and, above all, a fascination with the search for original roots, which are symbiotically connected to each other and cannot survive without one another.

Hana Nováková is mainly a director, holding a degree in ethnozoology too. I know Hana has dedicated her research on moose – a majestic animal and the largest ungulate. Seeing a moose is incredibly profound experience. Hana has been patiently recording the animal on camera and stories for several years, including legends. The moose is perceived by the native population as a female element – a metaphor for nature and mutual symbiosis.

Beuys’ intention has stepped in here too. The documentary Amoosed features the moose that changes people’s lives. The primal Mi'kmaq nation still living in Canada told the author that once upon a time – as is the case in mythologies – they made an agreement with the moose that it could give them his under a condition. But since humans were greedy, the trust of the moose was broken and man was left alone. By controlling everything, the man detaches himself from nature, which he needs. Hana introduces six different people from different parts of the world, for whom the sight of a moose and its encounter changed their views of nature. The story of the Russian farmer Sasha, who initially worked at the moose domestication station in Kostroma, is striking. One day something broke inside him and he realized that he wanted to protect the moose and restore their freedom. Further, the director shows an artificially constructed moose safari for tourists in Sweden or discusses the extinction of moose due to malnutrition in zoos. The moose, whose body structure is megalithic, has extremely high nutritional requirements, that include plants and special types of herbs. The moose from the flatlands needs a large space, where it can slowly and majestically wander around. The moose does not like being told to do anything. It is not used to large herds. The author presents a satire about human life and power: a person first needs to own and control everything, and then, just one look is enough, and everything changes. Beuys wanted to heal the society. So could a single species, a single experience, heal the society in order to develop sensitivity and understanding of nature? Can one animal affect the human psyche to the extent to realize that it is unfair to violate other living beings? A short piece of the feature film that was adapted for the exhibition will premiere the upcoming autumn.

The video essay presented by Denisa Langrová is an investigative search into wildlife of a specific place of the Milovice Nature Reserve in the Czech Republic. She uses “art research” as an alternative scientific method. The ungulates are at work here – enriching the soil with organic matter and contributing to the biodiversity of the site and, moreover, to adaptation to climate change. Based on the examination of photo trap data, the author discovers patterns resembling communication. To her, the recorded patterns become stories and messages that she re-interprets. The transcripts include patterns of wild horses, bison, and prairie dogs. The author draws on therolinguistics, a field that studies non-human languages, and which Ursula K. Le Guin elaborates in one of her texts (The Author of Acacia Seeds and Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Therolinguistics). In doing so, the artist creates space for new thought experiments about a world that has been hidden from us until now. The work critically reflects on both becoming wild and domestication and explores the boundaries between collaboration and exploitation. Why is it that an animal can learn our sign language and we ignore theirs?

The series on birds is presented by two artists: Magdaléna Manderlová, working in Norway, and Diana Lelonek from Poland.

Diana Lelonek is a photographer and multidisciplinary artist who develops stories of interspecies communication, cross-sectioning science and art. Her ecological commitment, with which she addresses the everyday issues of human approach to the environment, resonates in the work Birds Altar. Diana photographed dead birds on the Baltic coast – quite often killed from the food that the coast offered, for example the plastic. The two dead animals bring a visible theme of morte to the exhibition as well as contemplation on endangered and extinct species.

In her audio essay, Magdaléna Manderlová refers to extinct birds too. Through her memories, she sensitively captures the singing of the swift birds and canaries, combining field recordings with the spoken word and excerpts from the book Černá hvězda (Black Star) by Jan Balabán and Letters by Virginia Woolf. The memories create the atmosphere of summer, where birdsongs mingle with the smell of straw bales and plants swaying in a gentle breeze in contrast to the personal confession of dark shafts from coal mines. Deep listening is important, it encourages the audience to practice hearing, which generally hears too stereotypically. Through the audio essay, the audience can understand the environment, in which we communicate with humans as well as with other existing non-human beings. The realization that I ergo sum listen to other organisms and they in turn listen to me. The canaries (especially Atlantic canaries) gradually fade away, their voices are lower until they cease forever. It was common in the mines that the birds were introduced in large numbers inside the underground shafts to detect gas. If a canary stopped singing, it was known that there was a methane leak in the mine. The audio essay is the last reminder without answer. The audio essay is a final reminder without an answer. In poetic way, Magdalena refers to the issue of the inevitable disappearing and extinction of animal species caused by human activity.

The Finnish artistic duo Gustafsson&Haapoja, visual artist Terike Haapoja and writer Laura Gustafsson, work around the issue of animal rights and the rights of other non-human beings. The research project and the museum exhibition Museum of Nonhumanity show a cross-section of the history of inhumane oppression, slavery, exploitation and ecocide, with humanity’s constant pursuit of its own benefit at the expense of other species. For a long time, they have worked on the theme of domestication, especially in the works about pigs. Their work Waiting Room, is an audio recording of the pigs’ last evening before their slaughter. Escalating squealing of the animal traumatized in the piggery for fear of the morning. We can simply see the process of domestication in the pigs (from a wild, brown and hairy pig, to a pink and delicate piglet). The pig has a long history and used to be recognized as a sacred animal in the times of the Celts or Druids through great lore. For instance, in Egypt, the pig was a symbol of fertility. Staré pověsti české (Ancient Bohemian Legends) also depict a story of Bivoj, who conquered a boar and brought it to Vyšehrad to princess Libuše and her sister Kazi. A pig is like a human more than it may seem at first. The pig skin can replace the human skin in plastic surgeries. The pig is an omnivore that is highly intelligent and respectful of the behavior of others. The pig can see certain colors, but despite its small eyes, it prefers bright places. The pigs have no thermoregulation and therefore cannot sweat – they burn easily in the summer – that is why they cover their skin in mud to protect it. At the exhibition, the Finnish duo presents the personal story of Paav, the piggy who saved himself from being slaughtered. Unfortunately, his siblings were not so lucky. Paavo was not gaining weight (the domestic pig is the animal that can be fattened the fastest, 1 kg almost a day), so he was taken to the animal shelter in Saporomäki. The video (Untitled – Alive) shows the happy days of Paava the pig that lives to its days, sleeps, wakes up and caresses towards a man.

Zdena Kolečková is represented by the work V jezírku pohaslých očí (In the Pond of Glazed Eyes). They say that one glimpse has the power to knock you down. The set of watercolors represent a look of the eyes that observe you, or even stare directly at you. You look the death in the eyes and recap your life. Fixed gaze is a significant for animals, let alone for mankind. Mammals, reptiles or birds perceive it as a threat. When someone gazes at you, you want to disappear rather than be provoked by a stranger who encourages you to respond to their passive aggression. How does this non-verbal communication work on the plate? Will you look a dead animal in the eye? The macro-images of fisheyes in detail, which the author has documented for a long time, gaze at our responsibility. Do you feel awkward? Is the man really going to eat us and treat us the same way over and over again?

Many of us know fish only on the plate, in a rather shapeless form of fillets, which do not say anything about their body constitution. Children recognize fish by color precisely through fillets – they know that, for example, pink belongs to salmon or shrimp. They don’t know, and perhaps not even their parents, that salmon get their color through the food they feed on (crustaceans) and gradually color their bodies with the familiar pink pigment. In addition, it is a migratory fish that requires a lot of movement, but the waterways have been closed (due to artificial water regulation and obstacles) and this has prevented the salmon from its natural movement. Previously, however, this fish was a relatively rare and expensive meal on restaurant menus. Nowadays, it has turned into a large-scale farming machinery. As the consumption increases year by year, salmon no longer live in their natural habitat and “breeders” multiply them in cages and feed them artificially, which poses a problem for their body coloration. The food they are fed in the fish farms is not sufficient. Pink is not pink enough, so it is dyed artificially, often with toxic colors that include lead.

What is surprising is that of fish can be found on the menu in the vegetarian restaurants, especially in Germany, where fish is not considered a meat. What is it then? A dumb creature that, unless it screams out loud, we can kill in the most drastic way – electrocute it, freeze it alive or suffocate? Unfortunately, there is no legal legislation for fish and fishing in general. At the same time, it seems that the consumption in the Western world supports the largest fish farms which impacts the climate crisis – the waters are warming up, fish are dying. A recent report from a Norwegian newspaper stated that almost 80% of fish in the Norwegian seas have been caught.

The artist points out finger at society where omnipresent death, which we now isolate from life, has disappeared. As I mentioned before, animals perceive gazing in the eyes as a challenge to a fight. The dead fisheyes can do that.

The work titled Equilibrium by Dominik Gajarský closes the exhibition holistically. It was created as part of the Jindřich Chalupecký Prize in 2017, where Gajarský worked with the sense of smell and the symbolism of the color green. In the present exhibition, we focused more on the essence of his work and the new soundtrack edits. The moving image narrates two absurd animal stories that really happened. The anthropomorphized main characters – the goose and the snake – take on the role of the narrator in the two unrelated stories. At a certain moment, however, they meet and intersect. The first story is about the geese whose two sisters were killed, and she wanders in the search for them to this day, looking sadly at its own reflection in the cars at the parking lot. The second one is about a rare snake that helps saving a person from debts. The animal monologues written by the author are accompanied by excerpts from classic literature, such as Sadie Plant: Writing on Drugs from 1999 or the dystopian one Aldous Huxley: The Doors of Perception of 1954. This artist’s fable points to the issue of humanization and ownership of animals as manifestation of human culture/power, with reference to John Berger’s previously mentioned essay Why Do We Look at Animals? In terms of its intellectual and aesthetic message, I believe that Equilibrium depicts the genesis of relationship between the man and animal. Despite the art piece concentrates on general human emotions metaphorically attributed to animals – loneliness, fear, and separation – the emotions suggest that animals are not merely blind riders in our world, but living beings experiencing own feelings too, in my view.

To conclude, many of us do not visit zoos anymore and prefer other forms of entertainment. It is sad that despite the hierarchical structures in which we have thrown living creatures, including ourselves, we still have the need to act superior. The film about theorist, philosopher and professor Donna Haraway, Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival, shows that humanity is understood as part of nature, not separate. It shows her lovely relationship with her dog. We must strengthen our cohesion to an ever-greater extent, because by accelerating the extinction of animal species and violating the planet, we forget about the most important thing – our own sensitivity.

Tea Záchová