Satoshi Fujiwara

Bleached

Satoshi Fujiwara, Bleached, Print on blueback paper, 2017–2023. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

Advertisement

Satoshi Fujiwara, Bleached, Print on blueback paper, 2017–2023. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

Satoshi Fujiwara, Bleached, Print on blueback paper, 2017–2023. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

Satoshi Fujiwara, Bleached, Print on blueback paper, 2017–2023. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

Satoshi Fujiwara, Bleached, Print on blueback paper, 2017–2023. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

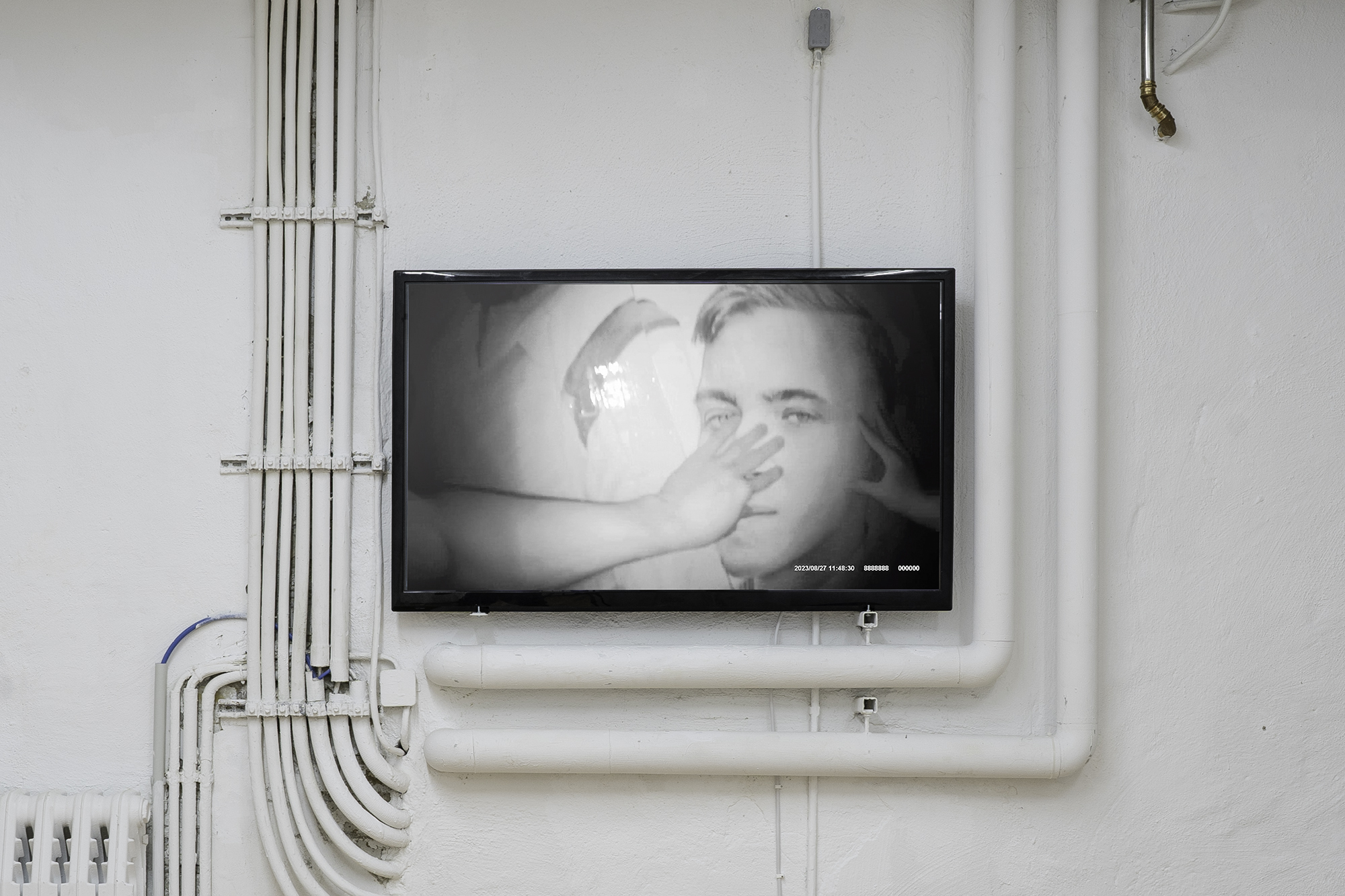

Satoshi Fujiwara, Haunted Tourist (After Hans-Joachim Bohlmann, Bodycam video, 0:40 mins, 2023. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

Satoshi Fujiwara, Haunted Tourist (After Hans-Joachim Bohlmann, Bodycam video, 0:40 mins, 2023. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

Satoshi Fujiwara, Kopernikanische Wende (Copernican Revolution), Bodycam video, 8 hours, 2024. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

Satoshi Fujiwara, Haunted Tourist (After Hans-Joachim Bohlmann, Bodycam video, 0:40 mins, 2023. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

Satoshi Fujiwara, Kopernikanische Wende (Copernican Revolution), Bodycam video, 8 hours, 2024. Courtesy the artist. Installation view of the exhibition Bleached at red, Berlin, 2024.

[…]

And on the lion rides a boy in white,

who holds on with a small hot hand;

meanwhile the lion shows his teeth and tongue.

And now and then there's a white elephant

[…]

- Rainer Maria Rilke, The Carousel (1907)

In the summer of 2017, more than 800 neo-Nazis gathered in Berlin Spandau to commemorate the 30th anniversary of Rudolf Heß' death. The former deputy to Adolf Hitler was found guilty at the Nuremberg trials and in 1987, after serving 40 years of his lifelong sentence, took his own life in Spandau Prison (Kriegsverbrechergefängnis Spandau). The memorial march took place in Wilhelmstraße, where the now-demolished Prison was located. In defiance of the government ban on displaying Nazi symbols in Germany, the participants of the march carried black-white-red Deutsches Reich flags, symbolizing their National Socialist and anti-democratic beliefs.

Within this charged atmosphere, Kobe-born and Berlin-based artist Satoshi Fujiwara set out to capture the event from up close: Disguised as an Asian tourist and armed only with his camera, he approached the neo-Nazis at close range to document the spectacle. These photographs became the foundation for his Bleached-series. Fujiwara meticulously edited them and removed any color and symbolic elements from banners, flags, clothing and skin of the participants. What remains are bleached white canvases and textures.

Fujiwara’s work therefore exists in the interplay of two seemingly paradoxical elements: While the journalistic technique of on-site documentation is crucial to his work in order to experience the spectacle and bear witness to the event, nor does he hide the fact that the images he presents are manipulated.

In times of deep fakes, most viewers are aware that photographic images have never been a particularly trustworthy source of information, much less so edited images. However, this common understanding does not stop us from feeling a certain immediacy resonating from these images: the artist's stylistic cropping brings us extremely close to the marching crowd, which is further emphasized due to the high resolution and the sharpness of the images. We stand face to face with the protesters and perceive this event as a factual reality. In other words, we become witnesses to the spectacle ourselves.

This is at odds with our knowledge of the artist’s manipulation process. By being altered, these images leave behind the inherent quality as “declaration of the seamless integrity of the real” (Rosalind Krauss) that the medium of photography claims. But through the manipulations, visibly implied by the series’ title, we gain access to something else, or to quote Jean Baudrillard’s description of hyperreality: “It is no longer a question of a false representation of reality (ideology) but of concealing the fact that the real is no longer real […]”. Seen through Baudrillard’s eyes, Fujiwara’s manipulated images are clearly constituting hyperreality. At the same time, the image’s blank spots and the title Bleached are betraying its artificiality, therefore unveiling and deconstructing their hyperreal condition.

The act of bleaching becomes a multifaceted phenomenon. Originally an act of iconoclasm of any Nazi symbolism, it also refers to censorship and the government ban on such symbolism. Here, the color white unfolds its many meanings: White as a color is associated with the immaculate clean sheet, the veil, new beginnings, innocence and hope. However, its “purity” often comes from exclusion or erasing of what was there before, it is related to “Auslöschung” (annihilation) and is an integral part of right wing racial theory of “white supremacy” and “white power”.

Fujiwara brings this discourse into the white cube of the art space, drawing a connection between Rilke’s aforementioned “white elephant”: While the poem is originally describing a carousel, the term can refer to an ever-recurring phenomenon, in this case the right wing tendencies throughout Germany’s history. Moreover, the white elephant is an established term for a troublesome possession that is expensive to maintain or difficult to dispose of; in this case referring to Rudolf Heß, who continued living in captivity for 40 years, long after the new German state wanted to shed all links to its Nazi past.

The topic of National Socialism is deeply ingrained in German history. Artistic treatment of this sensitive subject varies widely. In his 1965 series of portraits of family members during the Third Reich (Onkel Rudi, Tante Marianne) Gerhard Richter, similar to Fujiwara, chose photographic images as source material for his studies into Germany’s past. Richter departed from archival photos, which he then transferred to the medium of painting, thereby opening a discourse about guilt, personal fates and repressed memories. Fujiwara, however, aims at the opposite: His camera serves as a tool to capture neo-Nazis in contemporary society. Instead of blurring these photographs in a Richter-like manner, he sharpens them, and thereby evokes a distinct realism that forces its observer to trust the reality of the spectacle witnessed. Although the images depict a memorial march, Bleached is not primarily about memory. Everything we witness is located in close proximity to the viewer, a testimony of our contemporary society and times.

In this practice, Fujiwara found an unlikely ally in spirit: when asked about his planned, but never executed fake neo-Nazi rally in the Netherlands in 1993, Maurizio Cattelan’s response was extraordinarily serious:

“You should witness a real skinhead rally. I just take it; I’m always borrowing pieces – crumbs really – of everyday reality. If you think my work is very provocative, it means that reality is extremely provocative, and we just don’t react to it. Maybe we no longer pay attention to the way we live in the world. We are increasingly … how do you say, ‘don’t feel any pain’… we are anaesthetized.”

By choosing the medium of photography and emphasizing the testimonial character of the audience, Fujiwara is showing us a glimpse of this “extremely provocative” reality. Simultaneously, Fujiwara’s Bleached images can be seen as subverting Friedrich Nietzsche's famous saying: “Truth is ugly: we have art lest we perish from the truth.” Although, in a very cynical and ambiguous way, the artist presents a “whitewashed” version of reality.

Two videoworks are accompanying the Bleached-series. In Haunted Tourist (After Hans-Joachim Bohlmann), Fujiwara wears a police bodycam as he documents the hanging of his posters around public places in Berlin. The name of the work refers to Hans-Joachim Bohlmann, an infamous figure possessed by iconoclasm, who attacked and damaged more than 50 works of art from museums and galleries during his lifetime. The POV-like sequences of the video are repeatedly interrupted by scenes of protests of the year 2023, where fragments of arguments among protesters and police can be heard and seen. No context of the causes for these protests are given to the viewer, thereby renouncing any narrative structures.

Eventually, Fujiwara revisits the spots where he hung the posters and collects the remnants. These weatherworn, torn and crumpled pieces are presented in the exhibition in an almost sculptural arrangement. Like the medium of photography itself, they have an inherent indexical quality. They are artifacts that vouch for the factuality of the events shown on the screen. Acts of iconoclasm, whether caused by forces of nature or committed by people in the form of digital image manipulation or tearing down posters manually, appear to be an integral part of any reality.

A second video work, Kopernikanische Wende (Copernican Revolution), is shown in the same room on a much smaller screen. It shows first person footage of the artist working shifts as a dishwasher in a restaurant in Berlin. It consists of more than 8 hours of footage in a monotonous and repetitive routine, resembling the tasks of a typical workday. While the conditions have much improved since the line of work of the “plongeur” was famously described by George Orwell in Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), its social status has remained very much the same. These jobs are mostly invisible to the public and done predominantly by immigrants. Curiously, it is a common xenophobic claim that immigrants are stealing the livelihood of the local population. However, when it comes down to doing low paid jobs that are socially looked down upon like dishwashing, there is surprisingly little interest on behalf of these same prejudiced claimants.

berlinbookclub